|

by Rob Couteau

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

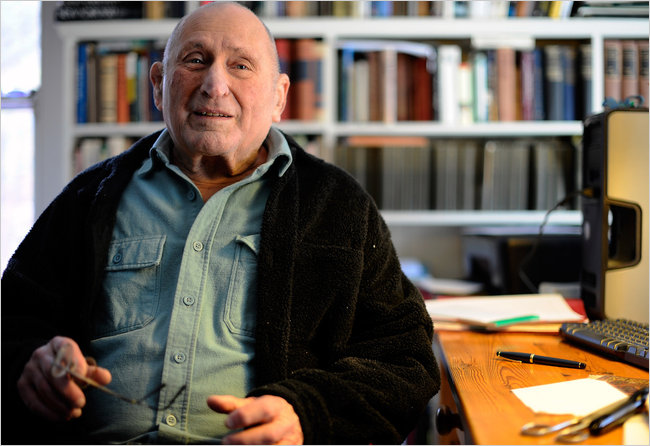

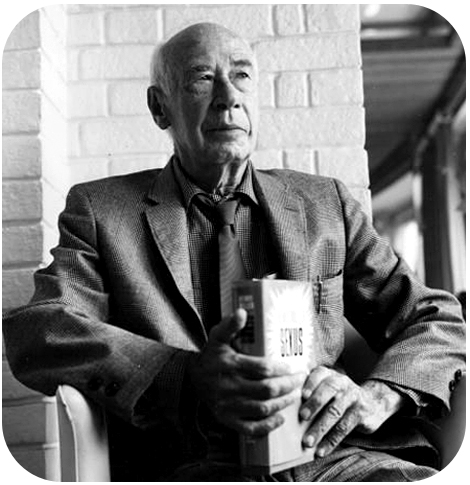

Awarded a Pulitzer Prize and a National Book Award for Mr. Clemens and Mark Twain, Justin Kaplan is the author of Lincoln Steffens, A Biography and Walt Whitman, A Life, which won an American Book Award. He’s also the editor of several editions of Bartlett's Familiar Quotations. Kaplan lives with his wife, author Anne Bernays, in Cambridge and Truro, Massachusetts. In 2002 they co-authored a “double memoir,” Back Then: Two Lives in 1950s New York. His latest work is When the Astors Owned New York: Blue Bloods and Grand Hotels in a Gilded Age (2006).*

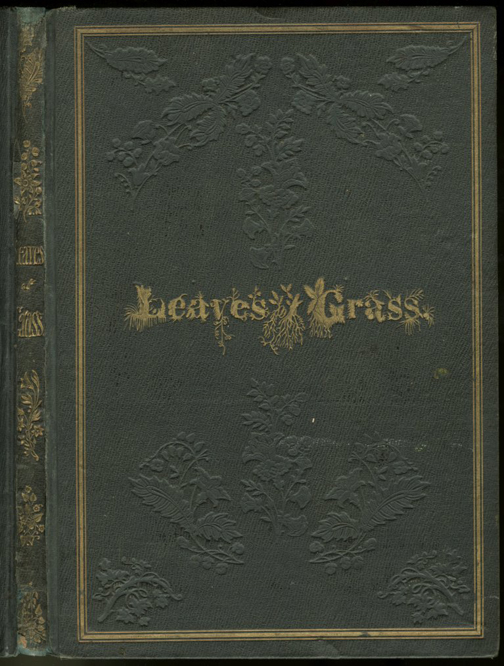

Rob Couteau: Joe, what led to your fascination with Walt Whitman? Justin Kaplan: That’s a big question. It was the mystery of the man, partly. That is, the sudden efflorescence of Leaves of Grass after what appeared to be a very unpromising first thirty years. There’s something vaguely sacramental about that. And he resists all attempts to get people to explain what he’s done. You just have to take it as a given. I really feel there’s a vaguely religious aspect to biography. Especially with creative people, you’re dealing with sort of a mystery. And you can describe the circumstances before and after some great innovation, but you can’t explain or describe the moment or the time that it happens, or the way it happens. RC: I’m glad to hear you say that; I agree with you so much about that. And I have some other questions about this mysterious aspect of it. Do you recall the first time you read “Song of Myself” and the effect it had on you? JK: Yes, I recall it very vividly. I was a student at the Horace Mann School for Boys, in New York. And we had as a text – the sort of high school edition – of Louis Untermeyer’s Modern American and British Poetry. That was the first time I had ever really read … I mean, I knew much of the familiar Whitman stuff: “O Captain! My Captain!” But this was a real revelation. That is, that beautiful lyric about being on the grass. And I never got over that feeling of “Wow. This is like nothing else.” I still feel that.

RC: You paint a wonderful portrait of Louis Untermeyer in your memoir Back Then. JK: Ah, good. He was a great man. He got pissed on a great deal because he was written off as a popularizer. But he did more than anybody else to really introduce modern British and American poetry. Even though he publicized himself along with his poetry. RC: I remember, in one of the editions of that book, he had his picture on the cover, along with the other “great poets” of all times. [Laughs] JK: I wouldn’t put it past him. [Laughs] But he deserved it. I mean, there were a lot of second-rate poets in his collection. RC: That’s a wonderful story in the sense that you ended up working with him, years later. It’s quite amazing, isn’t it? JK: It was fortuitous. RC: This is another very big question. Why is “Song of Myself” such an important poem? JK: Well, let’s say there are two aspects. One is historical. How original and innovative this poem was, especially if you read it in the context of the kind of poetry that was being written and loved in 1855. Tennyson, for example, who writes in an English that is literally English, whereas Whitman’s English is strictly … it’s very much like Huckleberry Finn. It’s the same sort of crossing over into the colloquial, and being able to handle the colloquial with great ease. That is, you don’t hear any grinding of gears. This is his natural idiom.

The trouble is, as Whitman got older and older, he tended not only to imitate himself but also to pick up some of the bad habits of Victorian poetry. He should have stayed at the age of thirty-six. RC: Walt read his father’s copies of Frances Wright’s A Few Days in Athens and Constantin de Volney’s The Ruins, and you say that Leaves “borrowed the insurgent and questioning spirit of these mentors along with literal quotations from their writings.” Were these the key contributions Walter Whitman Senior made to Walt’s intellectual inheritance? JK: I never thought of it that way. I suppose it was a contribution, but I couldn’t go beyond that. RC: And I understand the father also knew Tom Paine and read Tom Paine. JK: These claims really have to be looked at rather critically, because this is Walt writing in retrospect. And little things get magnified, and little encounters turn into anecdotes. It’s inevitable. So, I don’t know how much actual weight you can put to these stories. RC: I guess it’s impossible to say. One of his father’s favorite aphorisms was: “Keep good heart, the worst is to come.”

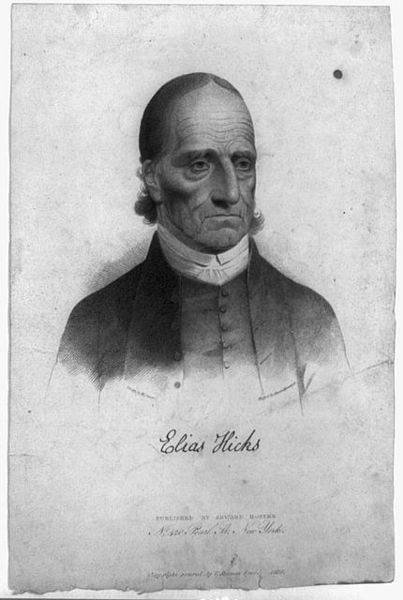

JK: That’s a cheery way to grow up, isn’t it? [Laughs] By the way, that reminds me of the advice of a publisher to someone whose first book is about to come out, and he’s complaining about the lack of excitement. He says, “This is the calm before the storm; before the calm, before the storm, the calm remains.” Well, anyhow, that’s a very downhearted piece of wisdom. RC: We know very little about the father, but what temperamental traits do you think he may have passed on to Walt? JK: I don’t see the two of them as being at all close. It’s the mother, in this instance, that was the vital link. The father is relevant as far as business and daily living is concerned. In fact, he very rarely refers to his father specifically, as I remember. RC: When we look at Walt as a journalist, he was a very opinionated man; he was a thinker, and he had strong ideas and opinions, and I’ve often wondered if there was some imprinting from the father in that regard. JK: I’m sure there must have been. Because if the father had definite opinions, Walt, as a beginning journalist, also had extremely definite opinions, some of which are kind of untoothsome. Some of those attitudes, judged by current standards, would be rather unpleasant. RC: When Walt was ten years old, he heard the preaching of a radical Quaker named Elias Hicks. You write, “His ‘passionate unstudied oratory,’ neither argumentative nor intellectual, turned into a naturally cadenced prose that at times seemed to strive to achieve the condition of poetry.” That description bears a strange resemblance to Leaves of Grass. Perhaps you could discuss how the phenomenon of oratory influenced “Song of Myself.”

JK: If you look at the voice in “Song of Myself,” it is somewhat addressing a group of people. It’s not private poetry. He’s maybe writing about private experience, but the stance, the communicating stance, is very public, and very open, and therefore very oratorical. In fact, there are places in the “Song of Myself” where he practically says: “Now, listen here.” He’s forcing the audience to pay attention. And remember, at that time, oratory was much more highly valued than it is now. We tend to be suspicious of oratory, whereas then it was the making of a politician, for one thing. RC: You say, “Hicks’s presence persisted in Whitman’s passion for oratory” and “in his wooing of ecstasy and in his fundamental creed, that ‘the fountain of all naked theology, all religion, all worship, all the truth to which you are possibly eligible’ was the single self and its inherent relations.” Is it possible that Walt’s very Eastern-sounding notion of a transcendental self can be traced back, in part, to Elias Hicks? JK: I’m sure you’re correct in that. Because Hicks becomes the absolute model of, let’s say, a transcendent person, especially in his oratory. He’s comparable in some ways to Father Mapple in Moby Dick. Remember the great, great sermon before the ship leaves? Mapple is sort of a fierce Elias Hicks. RC: You write that many of Walt’s “Chants Democratic” were “all too nakedly in the manner of the orator.” Would you agree that the first edition of Leaves was by far the best? JK: Absolutely. One of the horrible accidents that has befallen Whitman is that, when you say Leaves of Grass, people immediately think of this big, fat, 1892 edition, which has a lot of garbage in it. And the 1855 poem, or poems, eleven of them, are sort of buried in this enormous book. Yeah, I certainly think there’s no comparison between the 1855 version and the big so-called Leaves of Grass volume. It’s a pity, really.

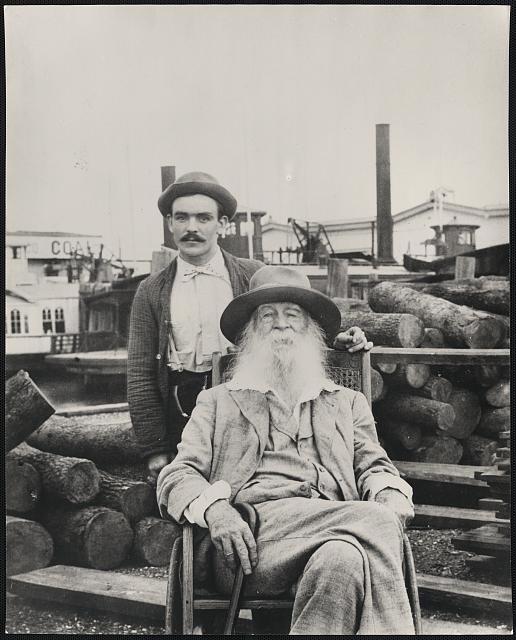

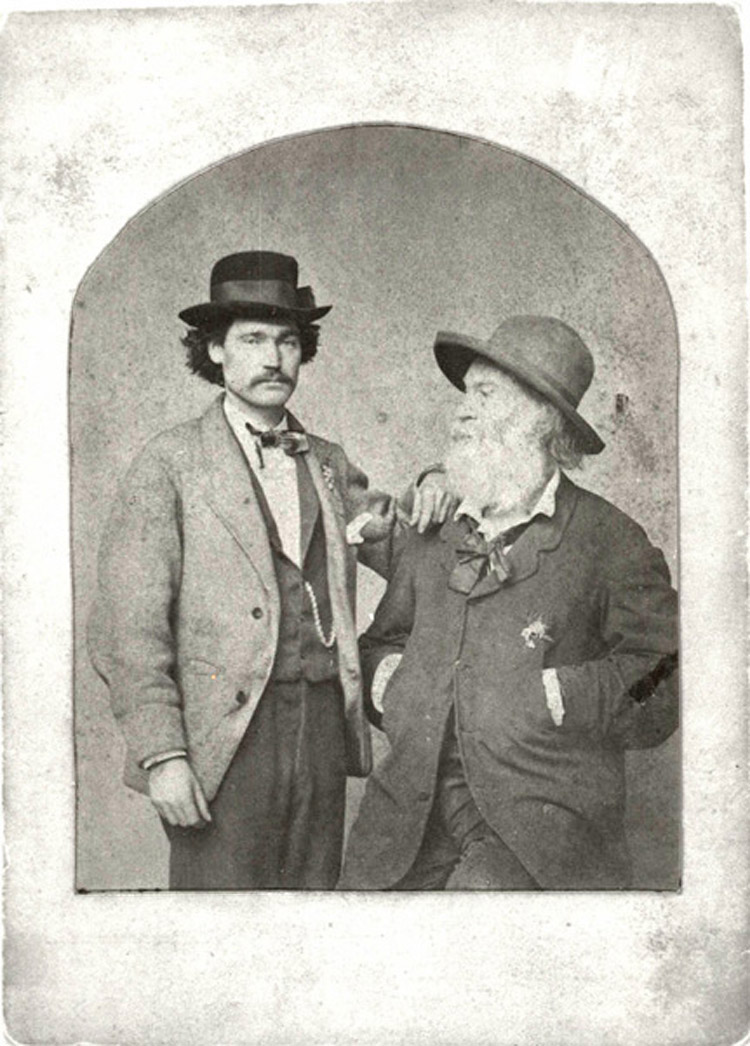

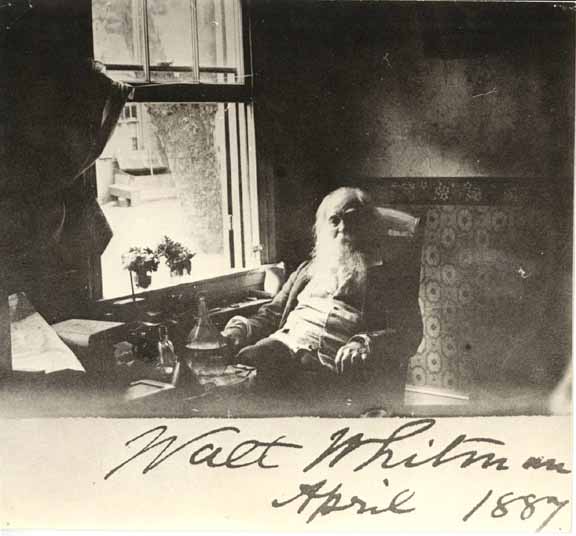

RC: It’s also a pity that he spent all that time constantly reworking it when he could have been creating something fresh. JK: Well, can you predict that? RC: No, you can’t. [Laughs] JK: [Laughs] You postulate that, but you can’t … RC: Well, this is another thing that you can’t really logically answer, but if you could speculate, what led to Walt’s relative decline as a poet after 1860? Was it the extreme physical toll the war took upon him? JK: It’s a number of things. It’s the toll of the war; it’s failing health; it’s strokes; it’s feebleness and so on. Also, quite aside from these disabilities, you can’t really project creativity. You might say he used up a great deal of it, and there’s a fair amount left over for the late poems, for the late poetry, but this is not a poetry factory. RC: Interpreting a single photo is a tricky business, but when you examine Harrison’s “Christ-likeness” of Walt, what qualities do you imagine it captures most strongly? JK: The intensity of the gaze. The very strange expression in the eyes. He’s looking at you, and he seems to be looking beyond you. Maybe I’m reading too much into that picture, but it’s a very Christlike image!

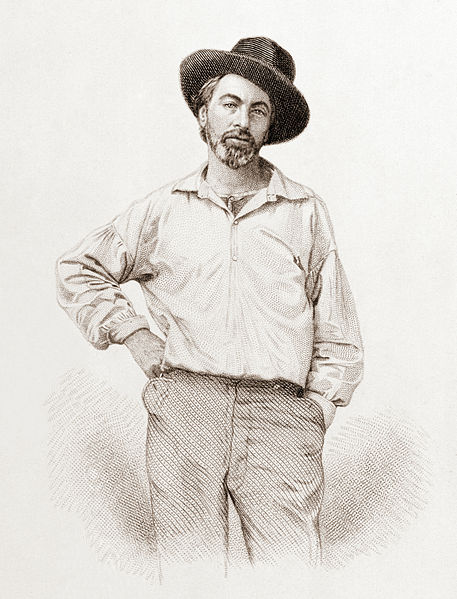

RC: And it’s an unusual image for that time, when everyone else is posing in a rigid, deadly way. He reaches out at you in that picture, doesn’t he? JK: Well, that’s true of that picture, and it’s certainly true of the frontispiece of the 1855 Leaves of Grass where he’s obviously an outside person, a worker. He’s not a library person or a literary person. RC: “One of the roughs,” as he liked to say. JK: Yes, exactly. RC: You write, “No other poet of his century wrote about the body with such explicitness and joy, anatomizing it at rest and cataloguing its parts, celebrating it as an instrument of love.” It might be interesting to compare this to the rather sexless, although equally profound, writing of Mark Twain. If Walt was clearly fascinated by sex, death, and rebirth, how would you characterize the literary keynotes of Twain? JK: Mark Twain was very reticent about sex and the physical, except when he was with his cronies. I’m not sure I understand the drift of the question, though. RC: I thought it would be interesting to compare Whitman’s over-the-top celebration of the body and of sexuality to Twain. When you read Whitman, the sacredness and sexuality of the body are so intertwined, and there’s also a great focus on death. And on psychological, or emotional, or spiritual rebirth.

JK: Yes. RC: I think these are the keynotes. So, if you compare these two writers, what are the keynotes of Mark Twain? JK: The keynote would be a sort of inspired skepticism about just about everything. Almost a religion of being skeptical. Of certainly not taking anything at face value. Certainly never accepting anything that’s pretentious or imitative. It’s a very compact value system, I think. RC: And a wonderful use of satire and irony. JK: To cut through all the ambient bullshit, yes. RC: [Laughs] That’s a great answer! I recently interviewed Robert Roper, who authored a book about Walt and his brothers during the war. When I asked him to discuss the nature of Whitman’s originality, he said: “That’s the big mystery of his poetry; where did that intimate tone come from? There were good poets” during this period, “but it wasn’t like your friend grabbing you by your shirt and saying, ‘This terrible thing happened to me last night. I saw this drunk get run over in the street.” That’s the kind of intimacy Walt evokes.” Would you agree with Roper, and can you think of examples of classical or antique poetry that feature such an intimate tone? JK: The only source I can think of as being comparable is Christian mystics. But poets in general … [Pauses] Alright, Keats’s “Nightingale” ode, which makes the transition from the poet standing there to a beatific and almost mystical vision of reality. And then it fades. As the nightingale goes away.* But I think Whitman is almost unique in this hyperreligious, mystical style. Where did it come from, as I suggested before, nobody knows. [Laughs] It’s a sacred mystery; it really is.

RC: That’s one of the things I enjoyed about your book. Yours was the first Whitman biography I ever read; I was about twenty-three at the time, and it had a great influence on me. One of the things I loved about it was that you really address the spirituality, and mysticism, and mystery of Whitman. And not everyone does. JK: I don’t see how you could write about Whitman without doing that. RC: Well, for example, with David Reynolds’s book, it’s almost like a vast attempt to trace every cause and effect in society to a result in the poetry. JK: It’s a very workmanlike, very thorough approach to Whitman, but it’s not transcendent in any sense. RC: You quote Henry Adams, who “asked himself ‘whether he knew of any American artist who had ever insisted on the power of sex, as every classic has always done; but he could think only of Walt Whitman…. All the rest had used sex for sentiment, never force.’” JK: That’s a great quotation from Adams. RC: It illustrates that it isn’t just the portrayal of sex that makes Whitman unique, it’s the poetic discussion of it as an inherent power and life force: even one through which spirituality is experienced and expressed. JK: Yes. RC: This lends him a kinship with certain writers of antiquity. I’m thinking of Sappho or Catullus.

JK: Yes. RC: Or of Petronius’ Satyricon. Would you agree that he seems to share a greater affinity with them than he does with writers of his own time? JK: I don’t see quite the relationship with Petronius; tell me how you see it. RC: When I read the Satyricon, it’s as if those two boys are captives, not of a particular relationship, but of a kind of cosmic power of lust and sex … JK: Yes. RC: And sensuality. But again, the main point being it’s not just the portrayal of sex that makes Whitman unique. JK: No, it’s not just sex; it informs the poetry. RC: That he attempts to address the archetypal power of sexuality as it’s expressed through the life force is something that’s very impressive in Leaves. For example, his poem “A Woman Waits for Me.” It’s not just about a particular woman, but it’s through this woman that the future of the whole nation is somehow assured. JK: Yes, he’s talking about the future generations, isn’t he? RC: Yes, it’s almost as if having sex becomes a patriotic act! JK: Yes. [Laughs] It’s a very powerful poem. RC: Writing about Walt’s life circa 1850, you say: “Whitman turned to the gospel of the self redeemed through art.” This notion of a “gospel of self” reminded me of something Joseph Campbell once said about how the modern artist – and not the religious institution – is the one who bears the new spiritual content. From your point of view, does Leaves primarily contain a spiritual message? JK: Yes. Very definitely. Not in any doctrinal way. [Laughs] But a spirit. And you can’t pin spirit down. RC: About halfway through your work, you conclude that, ultimately, “It is useless to look outside Whitman himself for the matrix or occasion for Leaves of Grass.” I like this very much because it honors the mystery of art and of the creator. Sometimes, there’s a tendency in biography to try to pin down every cause-and-effect relationship between an artist’s environment and his work, and, as every artist knows, this is not only impossible but it’s also misguided. I particularly appreciate your approach because, while it explored every possible artistic influence and connection, one also senses that you revere the mysterious, inexplicable spirit of artistic creation.

JK: Yes. You can write about it, as I tried to do it, without getting misty eyed. It’s a matter of, lets say, balance. RC: You say, “Supreme American inheritor of Romanticism, Whitman too believed the poet was the agency of a transcendent power and created ‘rapt verse’ in an ‘ecstasy of statement,’ ‘a trance, yet with all the senses alert.’” Although his manuscripts show he labored over his verse and continually edited and revised, is it your sense that the essential inspiration for much of his early verse came to him in a kind of trance state? JK: Yeah, I’d certainly like to think so. It depends on how literally you’re going to take that part of it. How autobiographical is your reading of Leaves of Grass going to be? And when he talks about that afternoon on the grass, you can’t help believing this is referring to a particular experience, which he generalizes from. But you can’t go too far with that, because poetry is not autobiography. RC: It’s coming from somewhere else, as well. JK: For the biographer and critic, it really comes down to a matter of respect for the so-called creative process. You can’t pin it down. You can’t pin it down; you can’t literalize it; you’ve got to live with it. There are pre-“Song of Myself” fragments that I found very moving and really indicative. In one of them – it’s a two or three-line quote – he uses the image of the sleeper. That is: “I’m now awake; have I been asleep all my life?” It’s a way of describing illumination. And I found that very crucial because you have the feeling that, yes, the same ecstatic mood that pervades “Song of Myself” is partly, if not rehearsed, at least recorded. RC: You say Leaves “was to celebrate the conquest of loneliness through the language of common modern speech.” About a year ago, I heard Barney Rosset* lecture … JK: Yes, I see he’s one of your heroes. He’s a great man. RC: I didn’t know much about Rosset until I saw a documentary that was recently made about him, Obscene. I was so moved by the fact that he sold off millions-of-dollars worth of beachfront property to pay for the court trials of Tropic of Cancer.

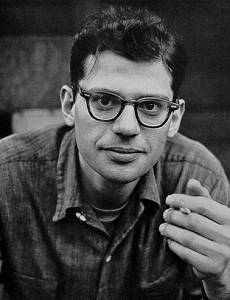

JK: He was a very generous man. RC: When he lectured, he said there was a direct line of literary descent extending from Whitman to Henry Miller to the Beats. In your Whitman biography, you spoke of how Leaves was to “celebrate the conquest of loneliness through the language of common modern speech” … JK: [Laughs] I thought that was a neat sentence; I was very proud of it. RC: It is a great sentence! And it brought to mind Rosset’s remark, and also that Ginsberg often said the Beats attempted to address this sense of separation and ameliorate it through poetry. JK: You mean, suggesting a conscious program? RC: Oh, I don’t know; I think Ginsberg probably worked through the same process that Whitman did, of just inspiration and so on. But I think, in reflecting on this, he thought it was a keynote of the Beats. In any case, do you feel there’s a connection between Whitman and Miller and some of the Beats? JK: Absolutely, yes. RC: How would you characterize it? JK: What they had in common? That’s a very tough question. I’m afraid anything I say is going to sound silly. [Laughs] But I feel very strongly the continuity of these guys. By the way, this is just a sidebar anecdote. But at the Horace Mann School, in the same era that I was introduced to “Song of Myself,” in French class, I was sitting next to a rather glum person named Jack Kerouac. This was a French class, and he never said anything. Can you guess why? RC: Why? JK: Because French was his first language. So he just sat there and endured the explication of French grammar. He was being seasoned at Horace Mann; they held him back for a year to season him for the Columbia football team. And then he broke a leg. RC: Was that your only contact with Kerouac? JK: Yes. As for Ginsberg, I liked him very much. RC: You had personal contacts with him? JK: Yes. For several years, every time I saw him, we argued over the same stupid point. You want to hear what it was? I’m quoting him: “You’ve got to listen to this! There’s a letter from John Burroughs, or one of those people, one of those associates of Whitman, saying: ‘Last night, I slept with Walt.’ And so, doesn’t that speak for itself?” [Laughs] And then, my side of the argument was: “Remember, when people visited in, let’s say, the 1870s, they didn’t have Motel 6.” RC: He was quite a character! JK: Yes. He and I were part of a crew doing a documentary on Whitman. I don’t know what happened to it. Anyhow, the first day of shooting, we were going to open with a scene from “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry.” And so, we were all lined up in the back of a ferryboat. The cinematographer was ready, and his camera focuses on Allen. This is to be the opening line of speeches. And he says, “Walt Whitman was America’s first mind-blowing poet.” [Laughs] And I said, “You just can’t do that! Not at the beginning, anyhow.”

RC: A friend of mine used to live in an apartment that was catty-corner to Allen’s in that building on East 12th Street. One day I was standing outside, waiting to be buzzed up. I was leaning against the wall reading a big, thick book: Anthony Summers’s biography on J. Edgar Hoover. Suddenly, I felt someone staring at me. About fifteen feet away, there was an old guy, ogling me. I went back to my book but then realized it was Ginsberg, so I nodded: sort of acknowledging our local poet. He went inside, and then my friend buzzed me up. When I went upstairs, they were in the hall, talking. I’d never met Allen before, and he turned and very meekly said, “Oh, do you mind if I ask what book you’re reading?” When I showed him the cover, he grew excited and asked, “Oh, is that the one where he talks about Hoover wearing a dress?” JK: Naturally, yes! [Laughs] He once got rather annoyed at me when I failed to recognize him because he had just shaved off his beard. And without the beard, he looked a lot like a butter-and-eggs salesman. Whereas with a beard, he was Allen Ginsberg. RC: I think Ginsberg’s best poem is his homage to Walt Whitman, “A Supermarket in California.” JK: Yes. RC: You agree? JK: Yeah. RC: Why do you think so? JK: It just is very powerful, and even moving, when Walt addresses the boy. He calls him “my angel.” RC: On the one hand, it’s such a visionary poem, and a poem that is just given to you, in some deep inspiration. And on the other hand, it’s such a carefully crafted poem. There’s not a misplaced word, or beat, or anything. Which Ginsberg very rarely achieves in his other work. JK: That’s a very good point. RC: You describe how Swinburne “rhapsodized about Whitman’s affinities with Blake.” Do you see a connection between Whitman and Blake? JK: I don’t see too great a contact between them stylistically. They both tend to be, let’s say, dithyrambic, at one point or another. Blake, when he got visionary, it became very institutional. That is, he organizes a sort of poetical church. It’s something Whitman would never do. The disaffection of Swinburne for Whitman is a vivid episode of turning on someone you absolutely worshipped and denouncing him in rather vivid invective: “Hottentot woman, drunk on adulterated cantharides.”* RC: You say that, for Walt, “the poet was the shaman of modern society, a master of ‘the techniques of ecstasy,’” quoting from Mircea Eliade’s classic, Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy, a wonderful book.

JK: Yes. RC: I recently read an article in the Walt Whitman Review by George Hutchinson, who explored the parallels between shamanism and the imagery of “The Sleepers.” JK: That is an incredible poem. I never quite got over it. RC: Hutchinson says that, while Whitman scholars often compare him to the Eastern Vedic tradition, this shamanistic imagery links him more to the Native American tradition. Perhaps you could comment on that and on the importance of “The Sleepers.” JK: To me, “The Sleepers” was important because he’s entering another dimension of being almost. And it’s a notion of … I can’t get over the simple image of the universality of “The Sleepers.” It’s not in a characteristic Whitman mode either. RC: You feel it goes in a much different direction than a lot of his other work, yes? JK: Somehow, it doesn’t quite belong in the 1855 Leaves of Grass. But that’s where it is. RC: Why do you feel that, Joe? Could you expand on that? JK: Let’s say “The Sleepers” is closer in understanding and in mood to the great section of Leaves of Grass with the episode on the grass. But if you look at the 1855 edition, there are all sorts of really disparate elements in it that not only don’t belong … I suppose the explanation is that he was in a terrible hurry to get it together. There’s a poem about the rendition of Anthony Burns, where you have a political level. And then, suddenly, you have “The Sleepers,” which is certainly not political. RC: For lack of a better term, there’s a deeply introverted quality to “The Sleepers,” whereas a lot of the other poems are very out there, in the world. JK: Yes. It’s a great poem, but it’s almost overshadowed by “Song of Myself.” RC: Horace Traubel quotes Whitman as saying “Swedenborg was right when he said there was a close connection … between the state we call religious ecstasy and the desire to copulate.” JK: Yes. [Laughs] That’s putting it in a nutshell, yes. RC: This is a concept that appears throughout the history of religious thought, yet it was lost upon the literary Brahmins of Boston. Walt’s friend James Redpath wrote to Walt: “There is a prejudice [against] you here among the ‘fine’ ladies and gentlemen of the transcendental School. It is believed that you are not ashamed of your reproductive organs.” What’s really striking about Leaves is how Walt focuses on the body, and on the sensual and sensory experience, as being synonymous with spiritual experience. Is it fair to say that, for Walt, physical ecstasy is the instinctual expression of the spirit? JK: I wouldn’t be that exclusive. [Laughs] RC: But maybe you could talk about the connection he draws between the two. This seems to be a keynote in Leaves, doesn’t it, that we should not be ashamed of the body?

JK: Well, that’s certainly one of the overt messages, if there is a message. You know: the overt message of Leaves of Grass, which is to bring the body out in the open, and not be ashamed. And those people who objected, for example, to the “Calamus” poems, on the grounds that it was overphysical, were really getting it all wrong. There’s something very comic about it. [Laughs] That is, they’re objecting to the explicitness about the body, but they don’t seem to realize that this is, in many ways, a very gay poem. But they’re so dumb that they don’t see it. RC: When we look at it today, it seems so obvious. And yet, back then, there were parts of Leaves that people objected to more, for sexual reasons, than to “Calamus,” right? JK: Yes. By the way, this was one of the problems I had writing this book. Because, occasionally, members of the gay community would say, “What the hell business do you have writing about our guy?” And then, straight people would say, “Well, the important question about Whitman was, “Was he or wasn’t he?” What a stupid question! [Laughs] I kept telling them that the matter of whether he was or wasn’t is so tired and meaningless that there’s no point in talking about it. You don’t have to prove anything. RC: In America, there’s a tendency to label literature that way. You go to a bookstore and there’s a section for “Gay Writers,” and so on. In France, it’s quite different. There isn’t this concept of gay writers or straight writers. It’s just: “Is he a great writer or not?” JK: Yes. I often think of my exposure to American literature here. By “here,” I mean at Harvard. I was just so naïve, and really so simple-minded. I mean, this is before the advent of, let’s say, “queer theory,” or any other stuff like that. We were missing a lot. RC: Walt was about eight years old when slavery was outlawed in New York. Although he was quite advanced in certain ways in his fight against racial injustice, he also “continued to believe that blacks in general were genetically and psychologically unfitted for ‘amalgamation.’” How would you compare Whitman’s racial notions to Twain’s groundbreaking work against racism in books such as Huckleberry Finn and Puddin’head Wilson? JK: When Howells describes Mark Twain as a de-Southernized Southerner, he again was getting it all wrong. Because there are instances in the Mark Twain story where he practically confesses that “I am a child of another era, and I feel very uncomfortable with black people.” Which would be condemnatory now. But he’s being perfectly honest.

Why does he have a black butler? He says, “Because I don’t like the idea of giving orders to a white man.” There’s a residue of “good old slavery times” in Mark Twain and in Whitman, as well. They both were very reluctant to deal on an equal basis with blacks, especially in New York. Howells calls him a de-Southernized Southerner, but he wasn’t. He was always a Southerner. RC: After reading your Twain biography, I was struck by how much less sympathetic a character he was as compared to Whitman. You show how Twain exhibited a pattern of blaming others for his own faults and misdeeds and attacking many of his closest friends, except those he depended on, such as his wife, Olivia; Henry Rogers; and Andrew Carnegie. Whereas Walt’s empathy brought him all the way to the Civil War hospitals. JK: Yes. RC: And at the end of his life, Whitman surrounded himself with close supporters and friends such as Horace Traubel. Would you agree that Twain was not as sympathetic a character? JK: This is going to sound funny. He’s not as grown up as Whitman. [Laughs] In many ways, he’s sort of an overgrown child, you know, exhibiting himself. Whereas Whitman doesn’t have that exhibitionism. Well, he does, but not in the same vaguely infantile way. RC: It’s more balanced, isn’t it? JK: Yes.

RC: Although Walt’s prophecies weren’t always accurate, I thought this quote from Democratic Vistas was indeed prescient. He says: “In vain do we march with unprecedented strides to empire so colossal, outvying the antique, beyond Alexander’s, beyond the proudest sway of Rome…. It is as if we were somehow being endow’d with a vast and more and more thoroughly-appointed body, and then left with little or no soul.” JK: That’s a great passage. RC: What would he think of the direction America has taken today, in its 234th year? JK: What would he think of what’s now known as American imperialism? Well, he’s very explicit on that point. Even in that passage from Democratic Vistas, there’s a reference to extending over to Cuba and Canada as well, isn’t there? Extending to Cuba. I wonder how Fidel would feel about Whitman. Anyhow, these are people of their times. And they don’t shed the social impress. RC: Yet, what’s interesting about this quote is, he ends it by saying “and then left with little or no soul.” JK: Yes. RC: I’m confused about this quote, because, most of the time, when Whitman talks about the expansion of America, he discusses it in a purely positive way. But in this instance, he ends it with this ambiguous line “and then left with little or no soul.” So, is he finally questioning it, or not? JK: No. I thought this was a reference to what Mark Twain called the Gilded Age. Because they were contemporaneous. And big money began to take over the railroads, and the factories, and so on and so forth. RC: So, he’s saying it’s OK to be this imperialistic, but we should do it with more soul. JK: Yes. Because I think, deep down, he believes the United States is the destiny of the entire world. You know, the “gospel of democracy.”

RC: Would he be shocked at what’s happened to America, in terms of the rightwing direction that we’ve moved in? And in terms of the kind of empire we’ve created? Would he be disturbed by it? JK: I think as it comes with a growing materialism and a growing social fragmentation, he’d be horrified. At the same time, given his feeling about blacks, he might feel that this is not a good thing at all. RC: You end the biography with two lovely lines: “Almost alone among the major American writers, he achieved in his last years radiance, serenity and generosity of spirit.” “An old man who never married and had no heart’s companion now except his books, he rode contentedly at anchor on the waters of the past.” How would you compare his final years to those of Mark Twain? JK: Well, I think that passage speaks for itself. Mark Twain’s late years may not have been quite so bitter as … you know, it’s very dramatic to think of Mark Twain as turning completely sour. But he certainly is a much less happy person in his old age than Whitman. By the way, that passage about being one of the only American writers to achieve wholeness and equanimity in old age: I originally had that passage somewhere at the beginning of my book. And then my dear friend and my editor, your friend Michael Korda, said, “Listen, you’ve got to warm up this story. And I’ll show you how to do it. Take that paragraph, and stick it at the end.” Somewhere in your interview with Michael, you quote him as saying he’s always been rather shy and had trouble being verbal. And I’ve known him for forty years, and I’ve never found that to be true! [Laughs] RC: In his memoir, he portrays himself as a shy young man. And I was really shocked, because, when I saw him lecture, he was almost aggressive: it was very powerful. The contrast was amazing.

JK: Yes. RC: It was interesting to compare his portrait of Max Schuster* to yours: the different ways you each described him. JK: Yes, we’ve done a lot of trading of anecdotes. We both loved him. RC: Your portrait was very warm. JK: I really loved Max. And I felt very bad because, in a way, I betrayed him by resigning to do my own work. He was very angry. RC: You mention this in Back Then. I thought there was real warmth; you had a great sympathy for him. JK: He was a very sweet man, deep down. RC: In Back Then, you say your first Freudian analyst wrote an essay that “disposed of Leaves of Grass as a product of narcissistic isolation, gnawing loneliness, and homoerotic libido.” You devote quite a few pages to describing the enormous sway Freudian ideas held for so many in the 1950s. How can we account for this? Was it due to a kind of mass psychological naiveté? JK: Yeah, Freud was extremely hot then. For many of us, we had the feeling that if you did not have an exposure to psychoanalysis, it was like never having gone to graduate school. It was obligatory, almost. RC: The 1950s was such an incredibly different time. If you speak with people who are only twenty years old today, they just can’t imagine what life was like in America, back then. JK: That’s the point we were trying to make. That in many ways, the Fifties are as distant from us now as the Gibson Girl* was to the Fifties. An entire shift in culture and in manners. RC: I recall, years ago, listening to an interview with the fellow who wrote The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit … JK: I knew him, yes. RC: He said the idea for the book came as a result of going to work one day in a brown suit, or a blue suit, and he was called into the office and told, “No, you must wear a gray flannel suit.” JK: It was true. If you paid a lot of attention to clothes, it was very important if you were wearing, for example, flannel trousers – which we all did – but it was important that the flannel be of the darkest possible shade. And the legs should be very narrow. And it should have a Brooks Brothers label on it. And that was your complete outfit.

RC: It reminds me of what you say in the Whitman biography: how, in the 1850s, you were expected to wear black from head to toe! JK: Yes. RC: Joe, thanks for your time; I enjoyed talking with you so much. JK: I know. It was a lot of fun. _________________________ * This interview was conducted on 22 December 2010. * Keats’s “Ode to a Nightingale" ends with the lines: “Was it a vision, or a waking dream? / Fled is that music: – Do I wake or sleep?” * Barney Rosset, the former owner of Grove Press and the first American publisher of Henry Miller, Samuel Beckett, and Jean Genet, led the legal battle to publish D. H. Lawrence's Lady Chatterley's Lover and Henry Miller's Tropic of Cancer. * Swinburne wrote: “Mr. Whitman’s Eve is a drunken apple-woman, indecently sprawling in the slush and garbage amid the rotten refuse of her overturned fruit stall: but Mr. Whitman’s Venus is a hottentot wench under the influence of cantharides and adulterated rum.” * Max Schuster was the co-founder, with Richard L. Simon, of Simon & Schuster, Inc. Justin Kaplan and Michael Korda each began their careers as editors working under Max. * A reference to Charles Dana Gibson’s turn-of-the-century illustration of the ideal American woman, known as the Gibson Girl. |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

For more literary interviews see: |

||||||||||||||||||||

Updated: 1 November 2012 | All text Copyright © 2012 Rob Couteau | Justin Kaplan, Anne Bernays, Swinborne, Keats, Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, Mark Twain, Walt Waltman |